Does Language Shape our Thoughts - Are We What We Say We Are?

The concept that language may shape and constrain our thinking processes has been discussed for more than 60 years. However until recently there was no real way of testing it. Recently researchers at Stanford University and at MIT have helped to understand whether this concept is a reality or not. This has been done using comparative studies of a wide range of languages from many countries including: Indonesia, Russia, China, Greece, Chile and many Australian Aboriginal languages. Linguistic techniques and grammar studies have helped to better understand these concepts.

The idea for testing this rests on the observation that languages are profoundly different and that the differences are very large and affect the grammar and concepts, not just the words and structure involved in nouns, verbs etc.

Some of the major differences can be found in ancient Australian Aboriginal Languages. Lera Boroditsky in her research found that a small Aboriginal community on the western edge of Cape York, in northern Australia had an unusual concept of space, giving directions and orientation.

Instead of basing concepts or space based on relationships to the body, they used a concept based on cardinal-directions related to the sun's passage across the sky throughout the day.

Instead of giving directions like 'left', 'right', 'back' and 'forward' which are commonly used in English, they used terms similar to 'north', 'south-east', 'east', 'south' and 'west' .

These terms are used at a range of scales - from referring to parts of the body and giving close and far directions.

They say things similar to "You have a fly on your southwest leg" or "Move the stick to the north northwest."

The normal greeting in this community is "Where are you going?" and the answer is often something similar to " Southeast, in the middle distance."

Obviously to be understood you have to stay oriented at all times, otherwise you cannot speak properly nor be understood.

Because space is such a fundamental part of thought, it affects other concepts because people rely on it to build other, more abstract and more complex thoughts.

The various representations that have been shown to rely on how we think about space are numbers, time, musical pitch, kinship relations, morality, and various emotions.

When the same group of people we shown pictures with a time theme, such as a crocodile growing, and asked to arrange them in order by age it was clear that their spatial concepts affected this task as well.

Most speakers of English arrange the pictures in order of age from left to right.

Hebrew speakers tend to order the cards from right to left.

The Aboriginal group arranged the pictures from east to west.

- When they faced north, the cards went from right to left.

- When they were seated facing south, the cards went left to right.

- When they faced towards the east, the cards were arranged toward the body, with the oldest ones further away.

Other examples of language differences are related to the perception of the passage of time.

English speakers prefer discuss the duration of time in terms of length (e.g., "That was a long talk").

Whereas Spanish and Greek speakers discuss 'amounts' of time, relying more on words like "little", "much" and "big" rather than "long" and "short".

An important question at this point is:

Are these differences generated by the language itself or by some other aspects of the culture?

Of course, the lifestyle, environment and cultural context of Mandarin, Greek, English, Spanish, and Aboriginal speakers differ in a host of ways.

How do we prove that it is the language they use, and its features, that generates these differences in thinking, rather than some other feature of their respective cultures?

People can be taught different ways of thinking about concepts such as time.

When English speakers were taught to think about time in terms of an amount rather than a length their thinking changed to more like the way Spanish and Greek speakers regarded the duration of time.

This means that when you learn a new language, you are inadvertently learning a new way of thinking.

Some other examples of language differences affecting the thought processes are:

Gender Differences Associated with Language

In Spanish and other similar languages, nouns, even for inanimate things, are either masculine or feminine.

In Russian the work for 'chair' is masculine and 'bed' are feminine. Does this gender assignment make Russian speakers regard beds as more like women and chairs as being more like men in some way? It appears that it does.

When investigators asked German and Spanish speakers to recount things having converse allotted genders the responses were as forecast by the gender assignment. For example, when various people were asked to describe a "key" (which is feminine in Spanish and masculine in German):

- German speakers used phrases similar to "serrated," "hard," "jagged," "metal," "heavy,"

- Spanish speakers used phrases such as "little," "shiny," "golden," "intricate," "lovely," and "tiny."

To describe a "bridge," which is masculine in Spanish and feminine in German:

- German speakers said "fragile," "peaceful," "beautiful," "elegant," "pretty," and "slender,"

- Spanish speakers said "sturdy," "big," "long," "strong," "dangerous," and "towering."

These differences occurred even though all the checking was done in English, a language without grammatical gender.

The conclusion is that the gender assigned to inanimate objects in the language affects how the speaker thinks about the objects.

It is furthermore echoed in art, for example German artists tend to illustrate death using a man, while Russian painters show death using a woman - which are the genders assigned to 'death' in these languages. Such influences of gender assignment are profound as it applies to all nouns.

This shows that linguistic processes influence fundamental thought processes, unconsciously shaping the way we think and conceive of things and the way we see the world.

Counting Systems and How Language Affects Concepts

A study of a Brazilian tribe found that their language does not recognise numbers greater than two. Their counting goes 'one', 'two' and 'many', much like the symbols for forest in Chinese and Japanese - 'three's a crowd' and three tree symbols makes a forest.

The members of the Brazilian tribe Hunter-gatherers could not reliably recognise the distinction between four or five things put in a row.

In a test the tribe members were asked to match a group of 4 or 5 objects presented to them with a similar number and arrangement of objects.

- For one, two and three things, the test group matched the pattern correctly.

- But for 4 and 5, and up to 10 objects, their matches were very poor, getting worse as the line of objects got longer.

- When shown a group of objects more than 3, the subjects could only poorly recall the pattern by duplicating it.

- When the researcher tapped on the floor three times, the tribe members were good at repeating it, but failed to imitate four or five taps.

This shows how language can affect how the speaker comprehends these counting concepts.

The Contrary View of How Language affects Thoughts Processes

Despite the limitations of language there is no evidences this stops its speakers from thinking anything.

Humans are adaptable and we can find other modes of filling the gaps inherent in the language.

The renowned linguist Roman Jakobson emphasised some vital notions about how the dissimilarities between dialects sway the way we think.

As he contended - Languages disagree in what they must express and not in what they can express and convey." The issue is that dialects sways our thinking - not because of what our dialect permits us to think, but because of what it customarily makes us think about or conceive of things we are describing or speaking about.

The constraint is a habit, rather than an obligatory restriction, and we can adapt the language to fill the gap. The holes in the language can be plugged and we are capable of changing the way we think about things.

- In English you may use the phrase "I had a lovely dinner a neighbour, yesterday", without the sex of the neighbour being clear in the expression.

- In French of German the sex has to be specified using the male or female form of 'neighbour'.

- English speakers do not have to consider the sexes of neighbours, friends, teachers and a host of other persons when they speak about them, whereas speakers of other languages are obliged to do so every time. If there is an issue then the English speaker can easily add a word to clarify the sex if needed.

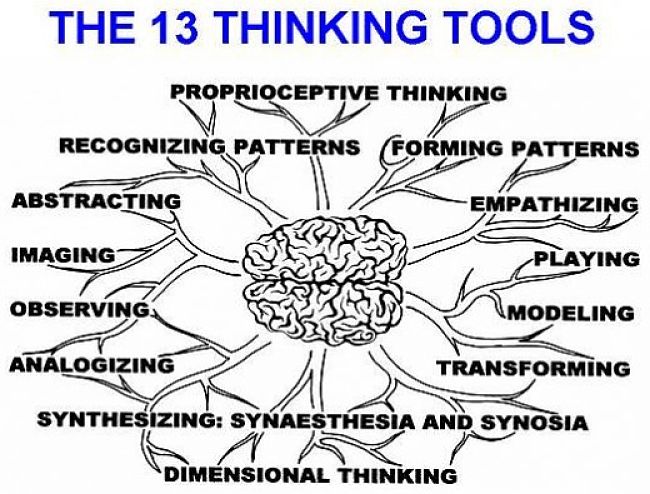

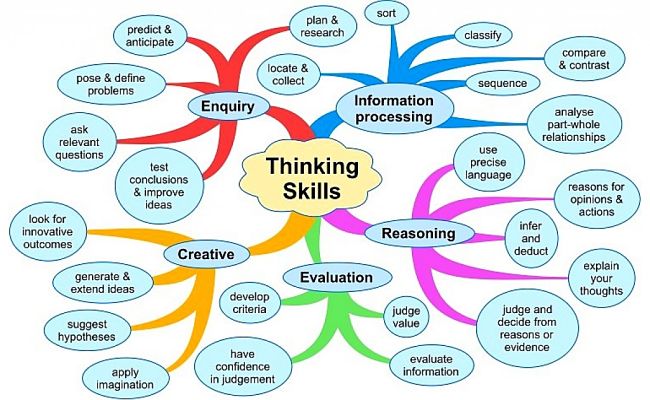

The vital aspect that is often overlooked, is that our thought processes are based on symbols (semiotics) and not on phrases and language at the fundamental level.

Semiotics is the study of symbols, signs or things that express meaning. Language is only one of many elements of human thought processes and we do not think in sentences or even parts of sentences.

Our thoughts are instead a combination of various symbols including: pictures, impulses, words, feelings, and the like.

The nouns, verbs other words, the grammar, and other features of language are all semiotic.

However many researchers regard thoughts and concepts as 'pre-linguistic', that is not fundamentally based on language.

The words and language are the way we express the thoughts, conceived without language into words for conversations and 'thought-sentences'.

All languages are also adaptable and analytical and this means that we can find combinations of words or expressions for words or concepts that are not in the language or are too new to be present.

The fact that languages constantly modify their grammar, invent new words and add words from other languages is a good argument is not constrained by the base language.

As the old German song says “thoughts are free” and many would argue that the human mind is not the slave of language.

The debate continues!

An intriguing study