Pros and Cons of Mandatory Bicycle Helmet Laws - What's the Evidence?

A Northern Ireland Assembly's decision to vote in favour of making the wearing of cycle helmets compulsory has re-activated a long standing worldwide debate about the merits of such laws. The British Medical Association has always argued that protective helmets and other headgear is a great way to prevent injuries and save lives. Opponents claim that these laws would discourage bike use and could be detrimental to the nation's health as less people would ride bicycles for exercise and for short trips. Likewise many have argued that the evidence supporting the contention that head gear protect the skull in the event of an accident are weak and poorly established.

Even in Australia wherecomplusory helmet laws were introduced 1991 (the first such laws for any country), there has been recent claims that the laws should be revoked. Two researchers from Sydney University claim the law does not work and should be changed. Their research showed that although there had been a drop in the number of head injuries since the laws were introduced in 1991, the use of helmets was not the main reason.

Strong Arguments For and Against Helmets

The reason was probably due to general improvement in road safety from measures such as random breath testing. They claim that scrapping compulsory head gear use would improve health rates and reduce injury rates because the increased number of cyclists on the roads would increase motorist's awareness of bike riders and motorists would learn to avoid them.

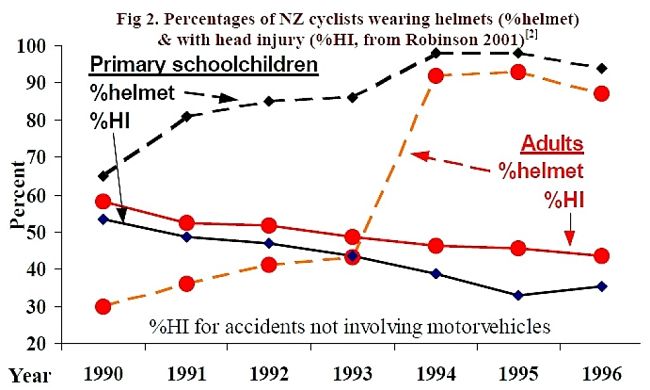

Dr Rissel compared the ratio of arm injuries to head injuries for cyclists admitted to hospital between 1988 and 2008. He assumed the ratio should have changed if helmet use reduced head injury rates. But the study showed that most of the change in the rates of head injuries occurred before 1991, that is before the laws came into force.

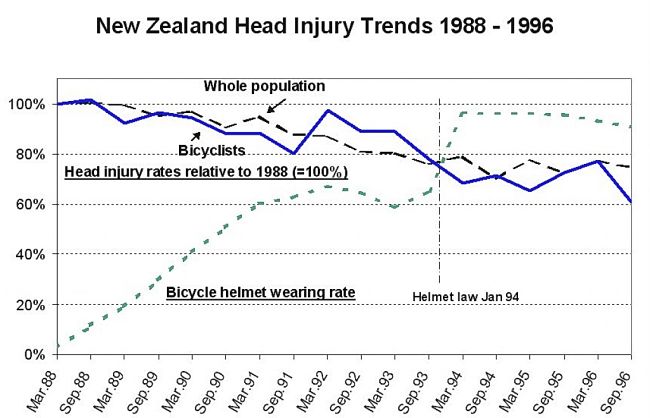

Also the trend for declining head injury rates continued without any major change when the laws were introduced (See figures below). However, Dr Rissel said that head gear was a good idea for many cyclists, especially those riding longer distances, and particularly for children.

------------------------------------------

[Update: As pointed out in the comment below, the Alex Voukelatos and Chris Rissel research has been found to contain many errors and cannot not be relied upon. In a later issue of the journal, the authors concede a number of mistakes and that their paper has serious arithmetic and data plotting errors. They apologised for the unintentional errors and any confusion that this may generate. However they said that they had obtained additional data from Victoria and Western Australia, which confirmed their original findings that general improvements in road safety were probably behind the decline in head injuries among cyclists. This saga highlights the contentious nature of the debate.

The issues associated with data trends and how they affect before and after comparisons are highlighted in the Figure shown below.]

------------------------------------------

The researcher who was instrumental in the move to make helmets use cumpulsory in Australia, more than 20 years ago. has challenged these research findings. Professor Frank McDermott, former chair of the Victorian Road Trauma Committee stated any sort of repeal would be very detrimental. He stated that the claim that the number of bike-related head injuries had remained similar since 1991 was dubious. He also criticised the method using 'ratios'. The ratio of arm versus head injury can be changed by either, and the lack of change may simply be due to there being a higher number of arm injuries. There was no specific helmet wearing data, and the injury data only relates to patients admitted to hospital. He says there is a lot of research which supports the wearing of head gear. He conducted a study on 1,710 Melbourne and Geelong bicycle casualties. About a quarter of them were wearing helmets and the head injury frequency was reduced about 50 per cent.

Christian King from Brain Injury Centre, Australia, agrees. He says it would be "an absurdity" if the legislation were overturned, or even challenged and prevention is better than any cure.

So who is right when you look at the available evidence?

Head gear for cylists is designed to protect the skull in the event of a bicycle accident. These devices were developed to reduce head trauma and brain damage while minimizing other consequences such as interference with peripheral vision. There is a raging technical argument, with no agreement, on whether head gear is helpful in reducing injuries, and whether the advantages are outweighed by their disadvantages in discouraging bicycle use. The arguments for and against making head gear use compulsory are strongly and bitterly debated by various interest groups. These arguments are based on differing interpretations of the accessible study papers, and on differing assumptions and biases pushed by those for and against. Moving from an association between to variables to establish a cause and effect is always difficult.

Helmets are Compulsory for Sport Cyclists

Historically, road cycle racing guidelines set by the sport's ruling body, Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), did not require that protective head gear should be worn. The matter was left to personal preferences and localized traffic laws. Most of professional road racing cyclists chose not to wear helmets because of discomfort and the extra weight of the helmets.

The first major move by the UCI to apply compulsory head gear use occurred in 1991. This triggered powerful disagreement from the riders and led to a riders' strike, that forced the UCI to abandon the idea.

Voluntary helmet use in expert ranks increased a little in the 1990s, the turning point was the death of Kazakh Andrei Kivilevin in March 2003 . The helmet-less Kivilev hit the ground after a collision and died from a serious skull fracture.

The new compulsory head gear laws were implemented on May 5, 2003. Initially riders were allowed to remove their helmets during final climbs more than 5 kilometres long. Later modifications were made so that the use of protective head gear was mandatory at all times.

No investigations have been released that show whether helmets have reduced head injuries. However it has been shown that modern head gear can decrease the aerodynamic drag on a rider by about 2% over a rider with no gear, giving a competitive advantage, and most riders support their use.

Bike Helmet Laws around the World

Several Countries have revoked their compulsory Helmet Laws and many don't have them.

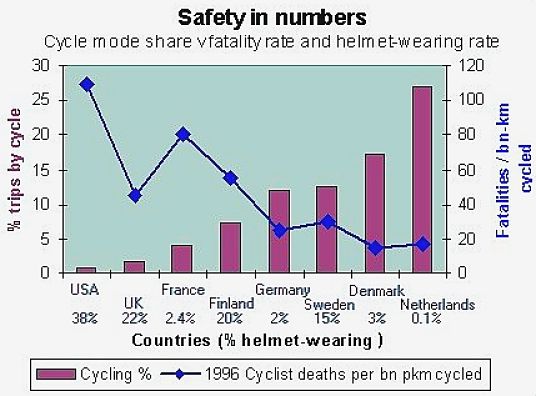

Arguments Against Laws for Compulsory Helmets

- Countries with the best safety record have low rates of head gear use - Denmark and the Netherlands have among the lowest levels and excellent safety records. The relatively low accident rate is generally attributed to safety in numbers, public awareness and understanding of cyclists, education, and also to separation from motor traffic. A comparative study of cycling in major streets of Paris, Boston and Amsterdam shows the differences in cycling culture: Boston shows the highest rates of head gear use (32% compared with 0.1% in Amsterdam and 2.4% in Paris). Amsterdam had the highest number of cyclists and rider density (242 passing bicycles per hour, compared with 55 in Boston and 74 in Paris). However, cycling in the Netherlands is generally safer than in any other country, and the Dutch have only about 30% of cycling fatalities (per 100,000 people) than Australia and other countries that have compulsory helmet laws. It has been claimed that in Denmark and Holland cycling is regarded as an every-day activity and motorists are used to them. Most people in Denmark and the Netherlands claim that helmet laws would discourage cycling by making it less convenient, less fashionable and less comfortable and that riders would take more risks.

- After Australia made bicycle helmet laws compulsory, about one third cyclists stopped riding their bicycles. In the UK between 1994 and 1996, in areas where the number of cyclists decreased, wearing rates increased and where the number of cyclists increased, protective gear wearing rates fell. Obviously the decline in injury rates after laws were introduced may be strongly influenced by the fall in the number of people using bikes.

- The (Australian) National Health and Medical Research Council in a related study of football injuries in 1994 noted that studies of cycling showed that helmets reduce soft tissue injuries but observed that while head gear may reduce scalp lacerations and other tissue injury, there is the risk injury rates could be increased because the gear increase both the size and mass of the head. Blows that would have been glancing could become more substantial and could transmit increased rotational forces to the brain and may increase brain injury.

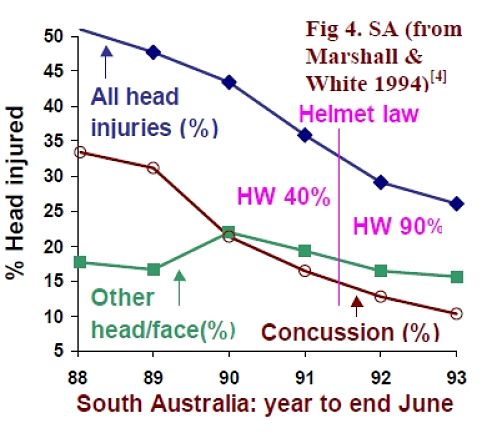

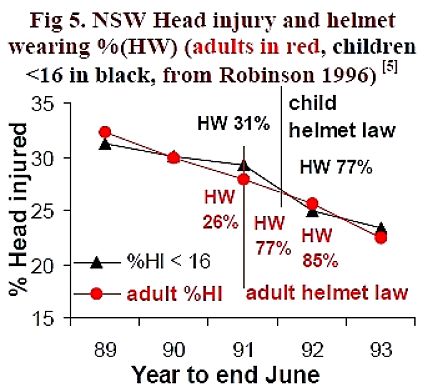

- While many studies claim reductions in head injury rates after laws were introduced, many of these studies ignore long term trends and other reasons for the change. This applied to many of the Australian research studies, where the was a long term trend for decreases before the laws were introduced, for all head injury rates, including non-bike statistics to follow similar trends and for the compounding effects of the decline in numbers of bike users on the roads after the laws were introduced.

- Bike helmets are designed to reduce the damage done by linear forces, by providing a soft yielding layer which reduces the maximum linear acceleration to the brain during impact. However, head impacts do not generally involve a direct square-on impact. Generally the impact is at an angle as the head hits the ground with forward momentum; or the head glances off the windshield of a motor vehicle. Such an impact is likely to generate rotational force on the head and brain, but the effects of these forces is unknown. There is a risk that helmets may actually increase both the brain and other injury rates because the addition of head gear will increase both the size and mass of the head. This means blows that would have been glancing and minor, may become more solid and thus transmit increased rotational forces to the brain and may increase diffuse brain injury.

- Another consideration is the differences in friction between the bare head and a helmet. A bare head and hard shell head gear are very similar and generally slide readily on impact. However, tests have shown that soft helmets tend to grab the surface of asphalt, rotating the head and producing large angular accelerations. This is a matter of concern given that most head gear worn are soft-shelled. However most of these are now have 'slippery' outer layers.

- There are cases of young children playing on or close to bunk beds,clothes lines, trees, play equipment, etc. suffering severe brain damage or death as a result of hanging by the straps of their bicycle helmets. To avoid these serious accidents, carers and parents should take care to ensure that children do not wear their bicycle head gear when playing unsupervised, or when using climbing equipment at home or in public parks.

- Bicycle use has been shown to have major large long-term health benefits and many countries and authorities have launched campaigns to increase the number of people who use bikes and introduced bike paths and other facilities. Estimates have shown that the health benefits of cycling outweigh the risks, perhaps by 20 to 1 according to one estimate. A reduction in the number of cyclists is likely to harm the health of the population more than any possible protection from injury. Introduction of compulsory laws has generally led to a decline in bicycle use and a reduction in the health benefits.

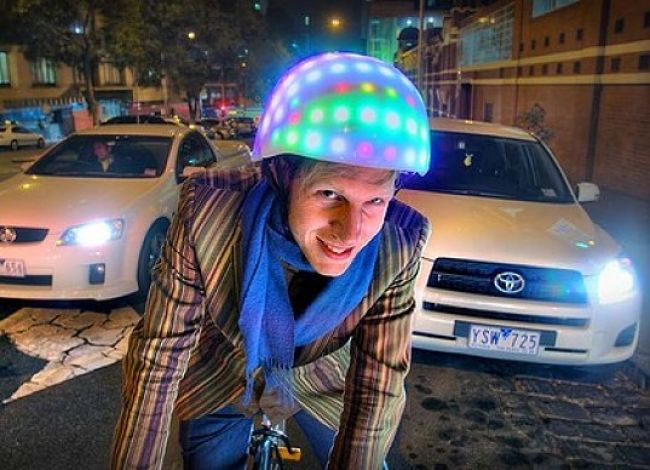

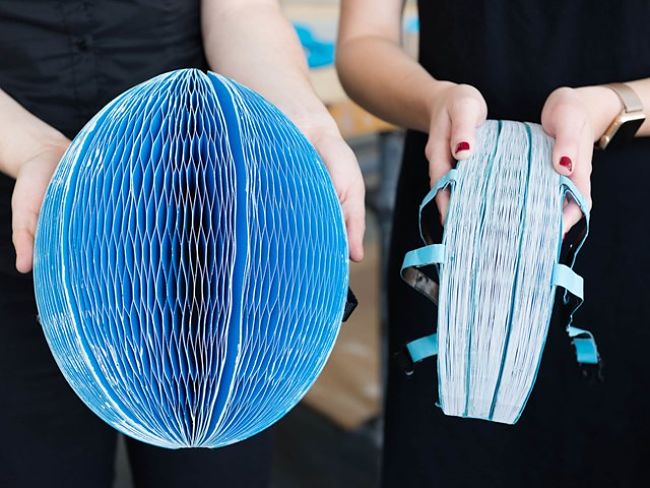

- Bike helmets are an additional expense and may make cycling less convenient; they are bulky and they cannot be stored securely with bikes and this is an added inconvenience.

- Bicycle head gear is seen as incompatible with some hairstyles many regard helmets as vexatious and ridiculous.

The Evidence Against Making Helmets Compulsory

Arguments FOR Compulsory Bike Helmets

- The World Health Organisation promotes the use of protective head gear on bikes as a strategy for preventing head injuries caused by falls and crashes. Head gear use is also supported by numerous organisation in the United States, including the American Medical Association and the American National Safety Council. The British Medical Association, in 2005, formally called on the UK government to introduce cycle helmet legislation.

- The Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research (SWOV) found contradictory evidence for and against bike head gear use, but on balance concluded "that a bicycle helmet is an effective means of protecting cyclists against head and brain injury", however the Dutch Government does not support compulsion or promotion.

- A study, much quoted and debated, by Thompson et al. included 5 properly conducted and controlled case control studies and found that head gear provide a from 63–88% decrease in the risk of brain, head and severe brain injury for all ages of bicyclists. Helmets were found to provide equal levels of protection for crashes involving motor vehicles (about 69%) and crashes from all other causes (about 68%). Furthermore, injuries to the upper and mid facial areas were found to be reduced by about 65%, although bike head gear did not prevent lower facial injuries. The review authors concluded from the study that helmets are an effective means of preventing head injury. However but this study has since been widely criticized for it's faulty methodology.The issue that raises is whether the behaviour of cyclists change as a consequence of wearing head gear in ways that offset the protective benefits.

- The evidence from time series studies in Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the U.S. shows that increased rates of head gear use produced from educational campaigns and various laws, were linked to substantial decreases in bicycle related head injuries. Given that helmets are very effective, cyclists would have to increase their risk taking by a factor of four to overcome the protective effect of helmets. This seems unlikely.

- The Child Safety Network estimated that about 200 US children under the age of 15 die each year from a bicycle-related injury. In addition, close to 9,000 children are hospitalized and 344,000 additional children are treated in emergency rooms from bike accidents. They suggested that bike helmets prevent about 50 - 60 % of bike-related head injury deaths, 65 % of upper and middle face injuries and 68-85 % of nonfatal head and scalp injuries.The CSN suggested that if 85 % of all child-age cyclists could be encouraged to wear helmets for 12 months, the lifetime medical cost savings for those children could total between $197 to $256 million.

- A systematic review by Macpherson and Spinks, published in 2007, examined the effectiveness of bike helmet legislation on bicycle-related injury and head gear use. The review authors concluded that there was good evidence that bike helmet legislation reduced head injuries among cyclists. Legislation led to an increase in helmet use rates and to a decrease in head injury rates. However, they suggested that there few quality studies that measure these outcomes and how possible reductions in bicycle use may have affected the results.

- A study in Floridabefore and after implementation of Florida's helmet laws for children under the age of 16, found a significant rise in helmet use among children, aged 5–13, after the law was passed. Also, there was a substantial decline in the rates of bicycle related motor vehicle injuries among children after the law was passed. Although there have been complementary educational and outreach activities in the county to support helmet use, it appears that the greatest increase in use occurred after the passage of the helmet law.

- A US study was undertaken to estimate the number preventable bicycle related head injuries (BRHIs) and associated indirect and direct health costs from bike riders not using head gear. The study found that about 100,000 BRHIs could may been prevented in 1997 in the United States, through the use of helmets.These preventable deaths and injuries represent an estimated $2.3 billion in indirect health costs and $81 million in direct costs.

- A Canadian Study showed that bike injuries represented about 5% of all injuries seen in the 5 years the study was conducted. The relative percentage of admissions was about 13 % for bicyclists, which was significantly higher than the 8 % admissions of all non-bicyclist children. More than 70% of injured bicyclists reported that no helmet had been in use prior to the accident. Face and head injuries occurred more often for bike riders who did not use helmets. The study supported the need to control injuries by using helmets.

- A Case-Control Study of the Effectiveness of Bicycle Safety Helmets was undertaken in the US that involved 235 people with head injuries, who sought emergency care at hospitals. The study found that riders with helmets had an 85 % reduced rate of head injury and an 88 % reduced rate of brain injury. The study concluded that helmets are effective in preventing head injury. Helmets are particularly important for children, because the majority of serious head injuries from bicycling accidents occur with children.

- Ekman et al. (1997) found, in Skaraborg County, Sweden, where promotional campaigns resulted in a substantial increase in helmet wearing rates, head injuries in children under 15 fell by 59% and non-head injuries 48%. For Sweden as a whole, child cyclist head injuries fell by 43% compared with 32% for non-head injuries. In Sweden as a whole, head injuries fell to 84% of non-head injuries.